Rocking the Plaza for Peace

The now thirteen annual reincarnations of the 9/11 Table of Silence Project, conceived and choreographed by Jacqulyn Buglisi and presented each year on the morning of September 11 across the entire main expanse surrounding the fountain at the center of Lincoln Center’s Josie Robertson Plaza, have arguably grown into the artist’s magnum opus.

The work already involved more than 100 dancers in its very first iteration, which marked the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attacks of 2001. This year the 152 dancers, 7 musicians, 5 acapella singers and dozens of support and live streaming staff, security personnel and volunteers of the 13th edition, not to mention ceramic sculptural artist Rossella Vasta and her principal fabricator Fausto Bizzirri, costume designer A. Christina Giannini along with Alessandro Gherardi and assistants must bring the total number of people involved directly in the various manifestations of the production to over a thousand across the life of the project. The dancers alone each year have numbered between 129 and 182 and have included adults of all ethnicities and ages with and without apparent disabilities. The youngest among them would not even have been born on that fateful day 22 years ago.

The project has spawned a commemorative book designed and produced by photographer Paul B. Goode in collaboration with Buglisi Dance Theatre, as well as a comprehensive series of videos by Nel Shelby Productions that document the development of the work year by year. Shelby, like Goode, has been a presence all along, and her annual video translations, livestreamed on Youtube, Facebook Live, and Lincoln Center’s own streaming service have now reached people in 235 countries/territories globally as well as all 50 states in the U.S.

In 2020, in the teeth if the pandemic lockdown, the Arnhold Dance Innovation Fund came aboard as lead financial supporter and the work bloomed anew. A reimagined Table of Silence featured a new “Prologue” limited to 28 dancers to accommodate pandemic restrictions and adding live performance by Daniel Bernard Roumain (DBR) of his “Our Country” and the spoken word composition “Awakening” created and performed by Marc Bamuthi Joseph. These artists reappeared in 2021 with 36 dancers while the “Prologue; Improvisation” section that opened this year’s 9/11 iteration included elements of the 2020 and 2021 reimagined 9/11 Table of Silence Project prologue with DBR but without Bamuthi Joseph.

Photo by Josef Pinlac: Visual descriptions of both photos at bottom below.

Lincoln Center has begun, over the course of the pandemic pause, to come to grips with its architectural and social justice legacy. It has, over that time, witnessed both the delayed release of Steven Spielberg’s remake of West Side Story set in a contemporary cinematic recreation of San Juan Hill, the neighborhood the complex supplanted, and the remodeling of what has been renamed David Geffen Hall with artist Nina Chanel Abney’s monumental “San Juan Heal” installed in its uptown-facing façade windows.

In considering the mid-1960’s opening of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in the wake of Robert Moses’ “slum clearance” of a poor but vital neighborhood, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that “Philharmonic Hall, the State Theater, and the Metropolitan Opera are lushly decorated, conservative structures that the public finds pleasing and most professionals consider a failure of nerve, imagination and talent… Fortunately, the scale and relationship of the plazas are good, and they can be enjoyed as pedestrian open spaces.”

In the decades since Huxtable’s words appeared, I have seen and participated in the use of the fountain plaza for Lincoln Center Out of Doors events, a huge nuclear disarmament demonstration, Midsummer Nights’ Swing, Met Opera film projections, David Michalek’s Slow Dancing installation, an artificial turf hangout, and Carl Hancock Rux’s Juneteenth extravaganza this June 18th, as well as the silent disco that it initiated. I have enjoyed most of these, especially MSNS and the work of the two artists. The art temples have been renamed for billionaires except for the Met. Nothing I have experienced there, however, makes more powerful use of what the American Institute of Architect’s AIA Guide to NYC terms “this travertine acropolis of music and theater” than the 9/11 Table of Silence Project in its most recent incarnation. (Does it seem a predictable omission that dance doesn’t figure in the AIA authors’ characterization of the “travertine acropolis” in spite of the fact that the home of constituent company New York City Ballet has been designed and has generally been used specifically for this discipline?)

Full disclosure: our Dancing Matters group had the privilege of accepting an invitation from Buglisi Dance Theatre to view the proceedings this September 11 from the balcony of David Geffen Hall. I have watched the ceremony unfold from the plaza level about a half dozen times over the years and have always found it moving. Only last Monday did the genius of Buglisi and her collaborators’ design and execution stand fully revealed to me. The choreographer’s use of architect Philip Johnson’s 12 tavertine spokes radiating from the fountain, the plaza at large, and the aprons of the Met and the steps leading up from Columbus Avenue, have developed continually over the life of the project. Last Monday this all seemed to work together with a bare bones but essential power that ultimately draws upon and projects what Buglisi calls the “mandala energy” of Johnson’s design. The intricacies of moving the performers in lines and patterns though and across this expanse maintained a mysterious but palpable tension throughout.

The most stunning revelation on this viewing, however, had to be the way the sound, mostly produced live and only intermittently with the aid of amplification, filled the entire acropolis to match the pulsing presence and movement of the dancers. Particularly effective: the blending of the five female vocal artists intoning their vocalese through large white paper hand-held megaphones. The impression of vulnerable humans set off by a vast formal cityscape found further enhancement in the relation of the Martha Graham reminiscent choreographic designs to the art-temple architecture. Centering this energy, Bell Master/Conductor/Principal Dancer Terese Capucilli and her mirroring bowl ringer and dancer Lauren Jaeger moved with a regal authority that punctuated the proceedings during their cross-fountain duet.

Martha Graham’s fascination with and reimagination of Greek myth from a female perspective proved a potent basis for this dancing. Both Buglisi and Capucilli, as members of Martha’s last company to whom the creator bequeathed queenly roles such as Jocasta, Clytemnestra and Medea, serve as vital links and heirs not only to Graham’s technique but her theatrical imagination. To see Capucilli embody this power and, together with Buglisi, draw this embodiment from within Jaeger, a generation younger, seems to reaffirm its place within a contemporary dance context. On the “tavertine acropolis,” the power of the Greek chorus and the basic elements of sound, sight and movement essential to the conjuring of tragedy toward catharsis could, in this moving ceremony and prayer for peace, all at once be glimpsed and fully felt.

I invite the other members of the Dancing Matters group to comment further as they may wish.

Upper Photo by Terri Gold showing the moment of silent prayer in which the dancers have opened their rounded arms beginning at shoulder level palms and faces lifted skyward in concentric circles on and around the central fountain.

Lower Photo by Josef Pinlac: Visual description: Looking south from a balcony perch, over 100 barefoot dancers in A, Chrstina Giaanini’s white surplices and white tights variously dance around the central black granite topped circle of the Revson fountain across the entire expanse of the Josie Robertson (main) Plaza at Lincoln Center joined by at least two identifiable singers in white holding large white paper acoustic megaphones to their mouths. The fountain burbles at the level of the black granite central disk upon which sit about 3 dozen of Rossella Vasta’s white ceramic dinner plates spaced at regular intervals. Twelve tavertine marble spokes radiate through the otherwise dark grey concrete floor of the plaza crossing four separate concentric tavertine rings each of greater circumference with the smallest hugging the base of the fountain. Visible in the background: broken white clouds in a blue sky over a part of the Midtown Manhattan skyline, the red brick Empire hotel, part of Dante Park, traffic on Columbus Avenue and, bordering the Plaza, the former New York State Theater with large blank muslin projection screens stretched almost entirely across its three main balcony openings. Between audience members lining Columbus Avenue and the plaza stands a line of evenly placed sculptural anti-vehicle barriers. Audience also fills the spaces under the balcony and the muslin screens with a solid line of nuns in white habits occupying half of the next to last portal to the right (west) in the image.

- Published in Dancing Matters

History Meets Its Future

Call it a village; an almost careless yet embracing hospitality. I experienced its warmth the moment I entered through the old wooden red chapel door wreathed with a drone cloud of bumblebees and stood at the north end of the Gothic Revival peaked nave of what began life in 1868 as the chapel and Sunday school of the 1855, renovated 1879, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which stands just to the north on the same campus across a patch of the graveyard that dates to circa 1702 and surrounds both landmarked buildings. Adding another chapter to this history, the chapel has housed BAAD! (Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance) since the venue’s move there in 2014 from the more recently landmarked American Banknote Printing Plant building in Hunts Point where it had pioneered an artists’ community that helped revitalize that neighborhood. Its presence amid the gravestones seemed to both provoke and fulfill a similar promise for the colonial crossroads of Westchester Square and the entire East Bronx.

The easy acceptance of three young children among the multigenerational assemblage of folks in chairs on small risers lining the long walls of the nave on either side of what would become the central performance area enhanced my perception of a sense of community in this space. Facing me, across the long central corridor of the performance area, sat a panel of artist-presenters along the south wall who included host/moderator Aimee Meredith Cox, Melanie George, Millicent Johnnie and Hank Smith. I had walked into the last 20 minutes of the first course of what I had described to my Dancing Matters colleagues as a four-course meal for the soul, only the last segment of which involved actual food.

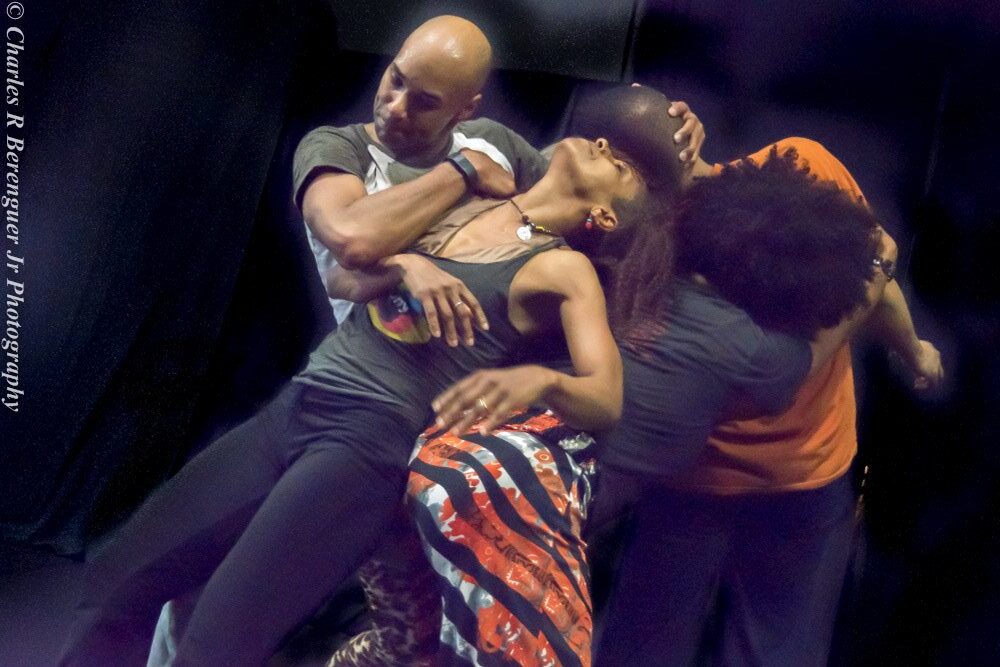

Image description: nia love leans back with Darrell Jones holding her shoulder. She is wearing a black tank top and black pants. He is wearing a gray t-shirt with black short sleeves. Photo by Charles R. Berengeur Jr.

Image description: nia love leans back with Darrell Jones holding her shoulder. She is wearing a black tank top and black pants. He is wearing a gray t-shirt with black short sleeves. Photo by Charles R. Berengeur Jr.

The question the panel along the south wall sought to address: “How has improvisation been a technology for Black thriving?” carried through the entire event and could be said to have been either eleven, 404 years or millennia in formulation. The May 13 unfolding marked the last of a year long celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Dancing While Black series co-directed by Kayla Hamilton, Marguerite Angelica Monique Hemmings, Paloma McGregor and Joya Powell alongside production and thought partner Shalonda Ingram and her team at Nursha Project. The 10th anniversary had begun with a similar three evening series a year ago, which like this year’s edition, began with two virtual presentations followed by a culminating live event at BAAD.

As the members of the panel shared their experiences and thoughts, a just over one year old roamed freely near me in and out of the performance area engaged and contained as occasionally appropriate by not only his mother but by other listeners on either side of the nave, while two somewhat older girls sat, sidled or slid between the knees of other women, one on each set of chairs and risers. The scene, reminiscent of that of a church during the liturgy of the word, served as the hors d’oeuvres.

While this testimony represented only the appetizer, the main course soon arrived as consecration when musician Jocelyn Pleasant on percussion and other instruments called forth the main celebrants Christal Brown, Lacina Coulibaly, Ana “Rokafella” Garcia, Nia Love, Dianne McIntyre, Jason Samuels Smith, and Marlies Yearby to occupy and sanctify the center of the room with an extended structured improvisation. Tolstoy wrote of art as “a human activity consisting in this, that one … consciously, by means of certain external signs, hand on to others feelings <they have> lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.” Even in the occasional awkward moments this performance manifested from time to time, the cross generational ensemble made these words flesh in ways that increasingly involved sharing with one another as well as those if us watching. In this Smith’s polyrythmic tapping and Rokafella’s breaking lent an extra breadth to the scope to the infectiveness of the dancing, but each of the others added her or his own flavor to the gumbo that we tasted as watchers.

Communion came as a kind of dessert as most of these witnesses became dancers themselves in a two hour dance party with active dj that followed the improvisational presentation. The entire six or more hour event leaned into the sense of communal involvement supportive of exploration within movement that one imagines that more than a decade of the Dancing While Black project has embodied and that the programming at BAAD! seems to epitomize. The full title of this final session had been given as DWB: Future: How We Thrive. As a harbinger of a possible post pandemic arts ecology the title seemed apt and its generous execution pointed with hope to a possible pathway.

As each of the Dancing Matters attendees danced their fill at the post party, we retired in twos and threes for our digestif discussion to the Mexican place that BAAD! Artistic Director Arthur Aviles had recommended on Westchester Square, one of seven La Estrellita’s whose burgeoning success hints at so much about the long slow recovery from lockdown evident in the New York City of this moment. We had invited the artists to join us at dinner and welcomed Rokafella along with her husband and partner Kwikstep to our table. Bronxite Rok did the majority of the ordering en español.

BAAD! and its borough might be seen as a place of pilgrimage among a large portion of the audience for live dance much as former Jacob’s Pillow Artistic Director Liz Thompson once characterized her campus in Becket, Massachusetts, that transfigured an old New England farm. One of our number intimated, in the course of our sojourn, that the last time he’d visited Westchester Square had been to leaflet against the draft during the U.S. war in Vietnam. I thought about that as I explored the cemetery surrounding BAAD! and St. Peters that contains graves from every U.S. conflict since its inception as well as about Myanmar, Sudan and Ukraine.

To arrive here for this extraordinary adventure from Brooklyn, one had had to allow for weekend subway work that had the number 6 train terminating at Parkchester, three stops short of East Tremont/Westchester Square. Our group, however, had shown the determination to reach this transformed village to embrace its history and unfolding future and be embraced by it in return. Mark Twain wrote of travel as, “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts.” Travel, like dancing, involves movement. I hope that my DM colleagues found this travelling as moving as I did, and maybe, whether they have or not, they will say so in writing on our Facebook page.

- Published in Dancing Matters

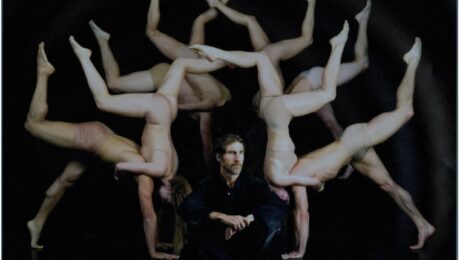

Momixing It Up

Moses Pendleton’s Momix, which he founded in 1980, while still creating as one of the cofounders of the cooperative ensemble Pilobolus, represents that rarest of species in American dance: a for profit company. An online search turned up nary another and an inquiry to Dance USA’s Director of Research set her off on a fruitless search for any others beyond the dance school and dance competition models.

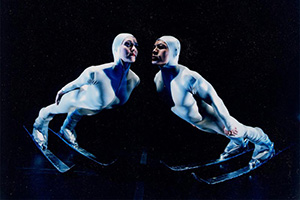

A female dancer (left) and male dancer (right) each lean sharply forward in extreme diagonals their feet anchored on skis, their bodies sheathed in full form-fitting long sleeved unitards complete with tight hoods tinted blue in the stage lighting against a deep black background and covering all but their faces which almost touch in Moses Pendleton’s “Millenum Skiva” created for his company Momix. Photo by Freddy Fernandez.

A female dancer (left) and male dancer (right) each lean sharply forward in extreme diagonals their feet anchored on skis, their bodies sheathed in full form-fitting long sleeved unitards complete with tight hoods tinted blue in the stage lighting against a deep black background and covering all but their faces which almost touch in Moses Pendleton’s “Millenum Skiva” created for his company Momix. Photo by Freddy Fernandez.

This may seem surprising, but perhaps it shouldn’t when one considers that Pendleton, ever the maverick, claims the fountainhead of his career as a showman as having been the Caledonian County Fair in the Northeast Kingdom of his native Vermont. Here he would exhibit his family’s dairy cows. Don’t know whether the family won any prizes and, if not, it surely could not have been for a lack of presentational skills. Pendleton’s been putting fanciful imaginary creatures (no cows that I know of) on stages across the globe for the last fifty years plus.

In a brief conversation in the aisle after the show, Pendleton proved as skeptical of dance community pieties as he always seems to have been. What becomes interesting then has to do with his singular creative focus on the locus of the human body in reimagining a universe based on the one we physically share with all other creatures and energies on earth.

The breadth of the appeal of his approach can be witnessed not only in the longevity of the Momix project on a touring and commissioning model that went out of style and functionality, if not at the demise of vaudeville, then just about the time that Pilobolus broke onto the scene, but also in the universal enchantment among the eighteen other Dancing Matters folks with whom I shared the experience. More importantly, I find it in the faces of the many children present. If this represents their introduction to dancing as a mode of expression, the kids might do as well with hip hop and/or the traditional dance cultures that Queens, the most immigrant rich borough among the five of an immigrant embracing and creatively energized city, brings to them. But in terms of stretching their imaginations, it might be hard to do better.

The show itself, so much a draw that Queens Theatre Director of Community Engagement Dominic D’Andrea remarked in a curtain speech that he couldn’t remember a larger Saturday matinee audience since the beginning of the pandemic, proceeded in bite sized pieces, perfect for kids and their parents. Most of these excerpts, drawn from the six shows that Momix currently claims as repertory, lasted between 3 and 4 minutes. They therefore represent a greatest hits collection of moments in medley and montage that almost insures its popularity and the overall length of show can prove both a blessing and a challenge to the audience described. Interestingly, “Paper Trails,” my personal favorite among these tidbits, occurring just before intermission, left a preponderance of the younger children asleep in their seats, exhausted, I presume, by the unfolding pageantry of the first half, the black light darkness and the lullaby quality of the mixtape score which included “Good Bye Brother” by Ramin, Djawadi: “Progeny” by Yvonne Moriarty, Gavin Greenway and the Lyndhurst; “Sorrow” by Klaus Badelt and Lisa Gerrard; “Wisdom Work” by Byron Metcalf.

Pendleton fronts an eclectic musical vocabulary to accompany his pieces ranging from contemporary sound artists such as these with Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major for the big finale. Let’s celebrate life!

I leave it to my Dancing Matters colleagues to overcome their shyness in responding in this democratic written critical discussion forum to speak up about the many other segments that they told me they adored in our round-table-picnic-in-the-park-post-performance confab, Queens Night Market having been cancelled as our ultimate destination that evening.

- Published in Dancing Matters

Crazier Than You

I

The late Bob Fosse invoked someone at the 1987 Tony Awards presentation, the year that he died at 60, as he introduced Gwen Verdon, still his wife, co-parent and longest-running muse and collaborator. As he phrased it, “It’s been said that the art of choreography is only 50% conception. And that the real test of your talent is getting five or six or however number of people in a room who are just a little crazier than you are and who can try to live out that, ah, that thing in your head. Sometimes, if you’re very lucky, you can find someone who dances it better than you ever dreamed it.”

The very present Elizabeth Streb, now 72, dreamed it, yes, and in many cases also danced it herself when first introduced. But as the evolving “Time Machine” program reveals, she has been very lucky indeed for some time and remains so.

The present company, billed as Action Heroes although I’ve heard Streb refer to them as dancers in rehearsal, retains only Co-Artistic Director Cassandre Joseph-Donnelly and Senior Action Hero Jackie Carlson from among the seasoned cast of eight who premiered the first iteration of this “Streb’s greatest hits” compendium on the outdoor stage at Jacob’s Pillow in mid-August, 2021. This pair may have been in grade school or younger when Fosse spoke. They almost certainly had not been born when Streb first performed Pole Vault and 7’43” in 1978, the oldest two pieces (billed Action Events) on the program that the Dancing Matters (DM) group took in on Saturday, March 25; the second show of “Time Machine’s” nine week run in the company’s home season in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I doubt that Streb could have dreamed of two more crazily accomplished and dedicated people to dance it any better.

Jackie Carlson in “Pole Vaults” Photo by Stephanie Berger

Visual description: Jackie Carlson, a pale skinned dancer (she/he/they) with a bright blonde fade haircut, black tank top with a large white and red Streb Action Hero “S” on the front, white Streb leggings printed in black and orange, and an orange stirrup wrap on her right ankle leans forward on her tippy toes against a 4 foot long closet dowel, spiral wrapped in yellow and dark green , balancing against their navel and the bare orange floor of SLAM. Behind him, in front of a cinder block wall, square open-latticed black metal apparatus legs frame a pattern of red, yellow, blue, white and smaller black squares surrounding 4 rectangular video screens. Thick red mats cover an adjacent part of the floor in front of a member of the tech crew behind a red console.

Joseph-Donnelly and Carlson have been with the company since 2007 and 2008 respectively. They lead an equally committed group listed as three other core company members, each of whom took on a solo in this program, alongside five other Action Heroes, at least three of whom joined the troupe in 2022. You could’ve fooled me.

In a former avocation as a jayvee college hockey player, heads-up team play meant everything to me when bladed sticks, hard rubber frozen disks and sharpened skates would be involved at maximum speed. The Action Heroes have many more objects of concern keeping them in sync and focused. They also seem to have had better practices than we did.

I like to roam whenever I can while taking in a performance, constantly seeking out the best angle with which to see the whole bodies of performers, including feet, as well as the audience in its moods and reactions. In this, the Streb Lab for Action Mechanics (SLAM) layout, in what had been an industrial loading facility, proved most accommodating. The sometimes bemused smiles and rapt attention I observed from the crowd, including those of not only my Dancing Matters colleagues but also that of a girl of no more than four in the first row on an adult woman’s lap, presaged the highly positive observations and occasional wonderment that characterized the DM post-performance discussion over bites and sips at the nearby Williamsburg Market.

Jackie Carlson (horizontal in bungee harness) pulled by other Streb Action Heroes in “Kiss the Air” finale.

Visual description: Jackie Carlson, a pale skinned dancer (she/he/they) with a bright blonde fade haircut, wearing a black tank top, white Streb leggings printed in black and orange, hangs horizontally at a slight diagonal, pointed toes up and head lifted at the neck toward 3 other similarly clad mixed race Streb Action heroes. Their feet just off the red mat over which s/he hangs in a bungee hip harness, the 3 other Heroes grasp her arms and pull her toward the audience directly behind them. About a dozen young children sit on the floor in the front row, some being protected by a brown skinned young man in black who reaches across them with his right arm to shield them while confetti fills the air, adults behind them smile and three of the adults hold up their cell phone cameras. screens. A white 12 foot wall stands behind the audience reaching part way to the ceiling while another Action Hero, a yellow “S” on his long sleeved t-shirt above yellow leggings and his face obscured holds an apparatus controller at the end of a yellow power cord.

The show reminded one member of a visual artist’s retrospective. Another compared the program to an evening of cinema short subjects. The group discussed another member’s irritation at the way the Action Heroes off the playing area would vocally encourage one another, particularly during solos. Having represented a fairly chirpy bench presence during hockey games, these interjections sounded refreshingly familiar to me.

The ”Time Machine” series continues Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, through May 21st, at the Streb Lab for Action Mechanics (SLAM) in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Action Hero rehearsals there remain free and open to the public in keeping with the Streb Extreme Action tradition of opening SLAM to the entire community to the maximum extent practicable.

- Published in Dancing Matters

Ronald K. Brown’s EVIDENCE at the Joyce!

We had all witnessed EVIDENCE

Sixteen of us then made it across the street to the Chinese restaurant on the eve of the year of the water rabbit, 4720, in China, 14 time zones ahead of us. According to the official Chinese state news agency Xinhua, tradition notes the rabbit as the luckiest of the 12 zodiac animals, representing peace and longevity. Kimmy Yam claims it also as evocative of the power of empathy. In Vietnam, the same day marks the eve of the year of the cat, a totem characterized as tranquil, realistic, intelligent, and artistic. All seven of these qualities had just been on display across 8th Avenue on the stage of the Joyce Theater, clearly visible through the front windows of the eatery that had stayed open late just for us.

We got to work helping Nina, our hostess, rearrange tables into a large irregular square in order to accommodate everyone in the group at a single platform within easy enough speaking distance from one another. This marked the first collaborative action that a Dancing Matters crew undertook as a community. As an omen of renewal and resilience that seemed to echo what we had just taken in, a concert consisting of three works by Ronald K. Brown crowned with an onstage appearance by the creator alongside Associate Artistic Director Arcell Cabuag at the final curtain bow, the physical nature of our initial communal activity augured well no matter which calendar you may consult.

Dancing Matters aims to create, foster, and promote democratic and collaborative critical response from across the wide and inclusive spectrum of dance related communities that the Dance Parade and DanceFest manifests each May. The group at the square table included several current and former professional dancers and choreographers, practitioners of the 5Rhythms meditative movement practice founded by the late Gabrielle Roth, at least one professional DJ, one creative writer with a movement background and others whose relationship to dancing might be characterized more ineffably. We went around the table person by person, each offering a few words that they might share with one another or a loved one as a way of conjuring and encapsulating an overall reaction to what they had just experienced.

Our professional DJ proved the first to comment on the formidable contributions of Brown’s collaborators in music and costuming. The curtain had parted on “Open Door” to begin the show revealing Andrew Antron seated at the baby grand piano audience left with the rest of Arturo O’Farrill’s band Resist made up of seven other members of the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra in a line across the rear of the stage back lit at the cyclorama and largely in silhouette. The choreography, originally commissioned and performed by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre in 2015, received its company premiere with these performances at the Joyce and the live presence of this fine ensemble along with their crisp Afro Cuban polyrhythmic sound served as a foretaste of the exquisite production values that would apply across the evening.

Our DJ did not neglect the music of Jason Moran accompanying the middle offering “The Equality of Night and Day,” which received its New York City premiere with these Joyce presentations. Nor did she ignore the Duke Ellington, Roy Davis, Jr., and Fela Anikulapo Kuti suite for the perennial favorite and crowd-pleasing finale “Grace,” commissioned, like “Open Door,” for the Ailey troupe (1999) and re-configured for EVIDENCE in 2003. Each recorded score sparked a similarly strong dialogue with the dancing and other stage elements.

Arcell Cabuag receives acknowledgement as Associate Choreographer for “Open Door.” Keiko Voltaire designed the costumes for this opus matching the imaginative flow if not the striking color of Omotayo Wunmi Olaiya’s designs for the other two works. Except for the projected photo collages curated by Deb Willis for “The Equality…”, no one at the table mentioned the superb set and lighting design and technical direction from Tsubasa Kamei that sustained throughout the evening, nor the accompanying text heard in recordings of the political activist and academic Angela Y. Davis. My oversight, I fear.

I have known and admired Ron Brown and his work, sometimes close at hand, since he, Dean Moss and I each presented duets as choreographer/performers decades ago on a single program of the Fresh Tracks platform at Dance Theater Workshop (DTW), which has since morphed into New York Live Arts. Yet this concert offered my first opportunity to ingest at one sitting such a panoply of his enormous creative output across the years of a generation and consider the significance of his contribution to the field not only in terms of his work over time but of his mentorship and development of a legion of strong voices among the dancers who have risen in his company such as Camille A. Brown, to point out just one.

It seemed to me that the mastermind of this home season within the warm and friendly confines of the Joyce engaged an interrogation in each of these three pieces, not only regarding individuality, community, and social justice as manifest in the movement of his company and the contributions of his collaborators, but among the technical discipline, tempos, rhythm and compositional elements that make dancing speak, especially as it draws from within bodies coming from across the African diaspora and beyond.

Besides the work of both Alvin Ailey and Camille A. Brown, between whom he represents a creative bridge, the choreography also recalled for me that of Garth Fagan in both its compositional invention and arresting deployment of stillness. I will leave it to other members of Dancing Matters to supplement as they wish.

Dancers in the Ronald K. Brown/Evidence company in “The Equality of Night and Day” at the Joyce Theater in New York.Credit…Andrea Mohin/The New York Times

Review: A Dance Searching for Harmony in an Unequal World

By Gia Kurlas

Jan. 18, 2023

“The Equality of Night and Day,” a New York premiere by the choreographer Ronald K. Brown and his company, Evidence, essentially starts out mid thought. A voice says, “And finally.”

It’s so no-nonsense that it practically sounds like a complete sentence. Spoken by the activist Angela Davis in a tone verging on weariness, the “and finally” urges the crowd — at least the one you imagine standing before her — to think about the larger picture, as she talks about issues that ail the United States, like “the assault against affirmative action” and “the increasing conservatism.”

The dancer Joyce Edwards, a silky powerhouse full of drama whether seemingly motionless or rippling her body with fervor, is poised center stage: She bends forward and rises back up with crossed wrists until her arms lift and bloom out like glorious wings. The lighting evokes the faded radiance of a sunset. As the other dancers gather around her, she clasps her hands, and we hear Davis ask that the people before her “think very deeply about what you can do to make a difference.”

Davis’s speeches are heard throughout this 2022 work, performed at the Joyce Theater, but better is its sparkling score by the jazz pianist Jason Moran. The music starts out spare and contained, but gradually builds with blistering, tinkering speed to get at, sonically, the urgency of not just one, but multiple generations that have faced oppression.

- Published in 2023, Dancing Matters

Engaging the Audience: Kinetic Light and Dean Moss model approaches

how do you welcome your audience?

“The actors never said hello to the audience,” theater director Anne Bogart quoted colleague Leon Ingulsrud as having complained in assessing a recent theater experience in the “Exit Interview” she gave the New York Times that appeared in November. “I thought that was really interesting” she continued. “The acknowledgment of that relationship, or how an audience interfaces, is the prize, I think.”

Two productions a week apart, each chosen as prospective outings for Dancing Matters (DM), illustrated ways in which some dance and movement artists have been developing their own approaches to the public they have been welcoming back as dancing continues to crawl out of the live performance drought that descended under the blanket of the pandemic.

To be sure, restrictions and preventative measures remain in force: both the Clark Studio Theater at Lincoln Center, in presenting Kinetic Light’s Under Momentum, and Danspace Project at St. Marks Church in presenting Dean Moss’ Your marks and surface, each required masking among all patrons and non-performing staff throughout one’s presence in the theater and lobby. If this represents a “new normal” of indefinite duration that somewhat mutes interaction, could what these artists have developed in engaging their audiences push back in intriguing and hopeful directions?

Under Momentum with Kinetic Light

Clark Studio Theater, 7th Floor of the Rose Building, Lincoln Center, February 24

My introduction to the world as designed by Kinetic Light (KL) took place in August during the NYC premiere run of Wired at The Shed when I happened to attend the only performance delayed for 45 minutes by technical difficulties. You’ll be flying wheelchairs and you’ve encountered technical difficulties?

Members of the audience had grown restive during the wait in the lobby but the verbal welcome curtain speech by a member of the KL team accompanied by two American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters proved disarming in both its warmth, beginning with a brief but genuine apology for the delay, and its breadth. It might as well serve as a model for the prize that Ingulsrud and Bogart seek.

The equivalent introduction at the Clark Studio Theater for Under Momentum may not have included an access enumeration of the seven (7!) channels of Audimance (app) audio description that KL and The Shed had made available for Wired, but the (large print) program, available for the asking, listed it along with other accommodations. Nor did the pair of onstage curtain speech hosts alongside their ASL counterpart, Daniel Israilov from SignNexus, face a testy crowd. Having walked through the sun drenched 7th floor lobby of the Clark, where another pair of friendly greeters checked you in, reinforced the masking protocols, and offered to answer any questions, one arrived in the Studio Theater to an audience ambience of relaxed comfort and friendly banter that represented a waking dream of thoughtful inclusiveness.

The two sold-out Kinetic Light shows that I have attended have both featured live captioning, tactile exhibits, sensory “stim” materials, expanded accessible seating and a quiet or safe “Chill Out” space with facilitated exit and re-entry available to audience members at any time throughout the performance. More in evidence for Under Momentum than at Wired: haptic soundtrack interpretation and the continuous presence of Israilov who became in effect a third performer opposite Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson, the featured duo and co-choreographers whose passages on top of, over, across and around the inventively protean deployments and configurations of Sara Hendren’s modular ramp designs underpins the impetus for the work. Israilov’s physicalization of the musical score at the audience left corner just offstage of the playing area closest to us added its own level of interest to the remarkable musical score.

Laurel Lawson lays across Alice Sheppard’s lap as she pushes Alice’s left wheel rim with both hands. They wear shimmery costumes in autumnal tones as they spin in their wheelchairs. Photo by Filip Wolak / Whitney Museum of American Art.

Under Momentum struck me as the most concentrated and focused introduction to the work of the dancer/choreographers and the KL Ensemble that I might imagine. I rued the fact that the Dancing Matters group proved too early in its evolution to organize quickly enough to snag tickets before the show sold out. The piece provided a clinic in contemporary dance creation and performance at the highest level. Standing in the exit aisle at the right side of the audience, having been encouraged like everyone else to stand, sit or move around by the introductory hosts, I found myself able to maneuver consistently in such a way as to intently study every move and transition on the stage while keeping Israilov’s dance-like ASL interpretation of the musical score easily in view.

This simple accommodation freed the experience from a one-way presentation vibe and enabled a more interactive approach sans the stifling and in many cases unnecessary and even counterproductive regimens of most Western theatrical events. Its liberating and humanizing effect allowed a girlchild of perhaps five to seven years old to lie on the floor in a gap among the wheel and power chairs in a taped off area at the very front of the audience surrounded by coloring books that she never made use of in my observation, so fascinating did she find the goings on in front of her that, chin propped on her hands over bent elbows, she could almost have reached out to touch.

Lawson and Sheppard began the piece without their wheelchairs in a slowly unfolding and developing adagio duet atop one or two of the longest ramp elements turned on their side. They followed this section with a suite of other sections mostly involving dancing in and out of wheelchairs punctuated intermittently with blue tinted half-light reconfigurations of the set by a crew of stagehands.

The subtly shifting and affective lighting design by ensemble member Michael Maag came to the fore in these transitions, supporting mostly in silence/ambient sound an air of unfolding mystery that served as counterpoint to the excellent recorded score drawn from multiple composers and supplemented with a haptic experience design by Lawson and realized with the help of David Bobier and Jim Ruxton ofVibraFusion labs.

Over the course of the work’s 80-minute duration with intermission, I felt an increasing excitement as if Lawson and Sheppard had enabled me to re-live and reinterpret my own earliest, though later in life than most dancers, training in modern dance technique and composition. Here I found myself re experiencing side falls and lateral stretches, theme and variations and even balletic set pieces that I have been witnessing ever since I got into performative dancing and dance making.

Sequential solos for Sheppard and then Lawson featured some of the most amazing innovations and reimaginings I’ve seen performed in wheelchairs; extraordinary feats of invention and physical power. At one point in her solo Sheppard executes a series of side rolls on the floor in her wheelchair tracing a circle around the center of the stage: a terrestrial reinvention of the ring of airborne barrel turns so commonly performed in the male principal dancer and soloist variations of ballet.

Laurel Lawson lays across Alice Sheppard’s lap as she pushes Alice’s left wheel rim with both hands. They wear shimmery costumes in autumnal tones as they spin in their wheelchairs. Photo by Filip Wolak / Whitney Museum of American Art.

Every traditional dance iteration transforms itself in the bodies and minds of these two and their collaborators. This complements inventions and passages, such as what I will call the Sisyphean mirror duet, made possible only by utilizing the chairs and ramps.

Compositionally, the works’ structural rhythm, variation and even the pauses for set redeployment along with the sound score all add to more than the sum of the parts. The subtle and supple development of the onstage relationship between Lawson and Sheppard as both individuals and partners created an understated layer of dramatic intrigue. Oh, how I wish the Dancing Matters group could have experienced and discussed all this with me.

Dean Moss’ Your marks and surface

Dancespace Project, St. Marks Church in the Bowery, February 24, 2023

Dean Moss, a black man wearing blue jeans and a lighter blue chambray shirt, leans to his left to counterbalance a bundle of white cotton sailcloth with a dark grey reinforcing hem enbedded with grommets threaded with black tie lines all bound up by thicker beige ropes as he swings the bundle away from himself in his right hand. Behind him loom the sacristy steps of St. Marks Church atop which sits a large portrait of a seated Moss dressed in the same clothes painted by Angela Dufresne . Photo from Moss’ “Your marks and surface,” Danspace Project, 2023. Photo by Ian Douglas.

The doors to the nave at St. Marks opened as usual before a Danspace performance and the knot of audience that had formed in the vestibule began to shuffle in. On the right side toward the midst of the main space beyond them, I glimpsed a trim middle-aged black man barefoot in work clothes – a pair of blue jeans with folded up cuffs at the ankles topped by a blue chambray shirt, long sleeves rolled up to the elbows. He dragged over his left shoulder and behind him a large sack of gathered cotton sail cloth complete with grommets threaded through with both black cotton tie line and fraying loose ended jute, hemp or sisal halyards of the type traditionally used for jib and main sheets on large sailboats. The lumpy cargo enclosed within this sailcloth appeared to be almost as tall as the adult human hauling it and at least twice as wide. The effort and energy required looked to be considerable from the way his body leaned forward and his legs struggled to move its weight across the polished wooden floor.

This became for me only the first of what dance writer Siobhan Burke in her excellent New York Times review recalled as “So many potent images <that> linger in the aftermath of Dean Moss’s” largely solo work Your marks and surface. In the lively nine-person Dancing Matters discussion that followed the show, over cocktails and compote, borscht, pierogis, and other delicacies at the nearby Ukrainian East Village Restaurant inside the Ukrainian National Home, the idea of images that linger and that help frame and reframe the affect of a movement work came into play.

The initial reaction of most members of the group to this affect ranged from dismissive to puzzled with a side of irritation. In the course of an honest hour-long back and forth, however, evidence of a relatively intense level of engagement among members of a dance audience, albeit negative at the outset, seemed to emerge. Palpable pain as well as the indelibility of the images seemed to bracket the debate.

Full disclosure: I worked with Moss for 2 ½ years as part of his six-person onstage ensemble for Nameless forest over a decade ago. In the course of that experience, I read a description of him as a “slippery” cross discipline artist. He can certainly be challenging in a way that I find leans to the good. I remember his fellow multi-discipline artist Ralph Lemon, invited to an in-process iteration of that work, challenging friend and colleague Moss concerning Nameless forest, still without its defining finale sequence. It remained, in Lemon’s view, “not transgressive enough” in the way that he had come to expect from a Moss opus.

Part of the edginess of a Moss work over the last 20 years or so has involved the ingenious and constantly evolving way he has involved the audience within the corpus of the work itself. Burke notes this within her review by quoting theater artist Young Jean Lee’s characterization of her sometime collaborator Moss as “the expert in that field.” When Kinetic Light proved a ticketing bridge too far for Dancing Matters, I warily suggested Your marks and surface as a replacement, carefully noting Danspace’s caveats that the piece “contains mature content” and that voluntary “audience participation <might be> included.” I told anyone who asked that I had no idea what to expect.

In retrospect, although I wish we could have seen KL as a cohort and discussed Under Momentum in the relatively posh and conducive confines of the remade lobby of David Geffen Hall, I have no regrets about the way things worked out and where we ended up digesting. I feel rather pleased instead to have provided an introduction to the work of a prickly old friend to people I have mostly met lately. As an auspicious bonus, on a pre-show visit to the restaurant I had discovered that a milonga would be in progress through two pairs of open double doors in an adjacent space down a few steps from the Ukrainian dining room and, in true DanceFest fashion, social dancing would accompany our late dinner and discussion.

It came to pass that I alone among our group became an audience participant in Your marks and surface. I had already claimed what I considered the prime “escape and audience observation” perch in the end seat of the top row at the southwestern (narrow) end of the risers facing into the nave, having discovered that most of the audience would be arrayed along the long east southeastern wall approximately 45 feet to my right. Already enjoying the relative freedom of movement that this “escape seat” would afford me, I had begun to roam, greeting other performers and friends from Dean’s previous works, second and third cousins from his extended artistic family network.

I had noted that some of these cousins had been receiving a Moss escort around the now abandoned bundle resting almost directly in front of my seat near the southwest corner of the nave. I felt safe, however, from his attention until, while chatting with David Hamilton Thompson, I felt his hand on my shoulder inviting me into sojourn. This tour progressed as completely natural up to a point. We began chatting and laughing as old friends and Dean’s manner and interaction remained friendly and forgiving throughout except when his hand around my shoulder or waist gently but firmly reminded me to keep walking or seemed to tilt me slightly off balance on my feet.

This admonished me that Moss may prefer to keep almost everyone, audience and performers alike, just a little on edge. More than once during the making, run and touring of Nameless forest I had remarked that part of the challenge of preparing that work involved letting a good deal of what I had absorbed through my professional dance training fall away temporarily to keep everything as alive as possible within the relatively strict structural limitations of the set and Dean’s choreographic designs. It seemed that whenever a sequence began to approach something people might begin to recognize as “dance” Dean would twist or break its form to keep everyone alert and creatively uncomfortable.

This ethic extended to envelop not only we six performing among the fresh dozen or so folks at each performance whom we had seduced, cajoled, beguiled or otherwise convinced, to join us onstage and take part in they knew not what and about which we could only make a practiced and educated guess that we could not reliably share with them. These recruitments took place during the audience takes its seats interim corresponding to that of the Your marks and surface’s walkabouts. Like Moss in the latter piece, we would already be found onstage as the ticket holders entered the theater proper.

Upon my release from our walk and return to my seat, I came to believe that this might be the most intimate and effective way of greeting and welcoming old and new friends and colleagues at the top of a show that I had ever seen or experienced. The once-around-the-stage stroll had a way of taking into the creator’s confidence some of us who had become familiar with Moss’ process and proclivities, as well as others who perhaps might not. Unlike the house opening sequence of the Broadway show Once, which allowed the paying customers to climb onto the stage boards and order a pint from the working taps of the pub built as the stage set prior to the cell phone announcement and the dimming of the house lights, the auteur/performer and not the patron determined the protocol here. (I never noticed whether a ramp or other accommodation had been offered in the Once gambit, while here the single level from the vestibule to nave would obviate such a consideration.)

Siobhan Burke has more than adequately described a great deal of the rest of the proceedings and I prefer to leave any outstanding observations and other resonant thoughts to other members of the Dancing Matters cohort in the comments below. I invite and welcome your input with a couple of parting notes:

Our post performance discussion reinforced for me how much the perception and processing of any challenging aesthetic depends on one’s perspective and often preconception. “Do you consider this dance?” has become an oft repeated and not unwelcome question since the heady days of the Judson Dance Theatre and, I might speculate, perhaps for eons before then. For Your marks and surface this implicated quite literally my choice of seating.

Shooed back into my chair by the stern and watchful house manager, I found myself still situated ideally to be able to watch both the action and most of the audience for the duration of the proceedings. But from the unwrapping of the original bundle to reveal a sculptural serpentine pyramid shaped mound within, a mound that would much later itself be unwound to reveal a softly writhing red orange shag bag with a body inside, I did not, from my angle, perceive the bare foot sticking out from the mound in the direction of the bulk of the crowd and plainly visible to most of the rest of my DM companions. This allowed me to fantasize about the contents of the bag that appeared revealed under the chair that served as the armature for the mound-pyramid long enough to wonder, when first seeing it move, whether it might be a collection of Roomba tribble-like balls in spite of my awareness of the credited inclusion of the dancer Sawami Fukuoka as a performer in the piece far in advance of the show. I had even seen some of Moss’ posted video work with her leading up to this piece. Fool me twice, shame on me.

In a related exercise in perception, I took notes across the duration of the event of the kind that I have not taken since giving up my four year stint as a mostly summertime dance critic for a daily newspaper. I deployed this tool in preparation for the post-partum discussion that follows as a feature of every Dancing Matters adventure, still stung by the humiliating experience of trying to recollect from memory for an academic paper the sequence of Moss’ johnbrown (2014), his successor project to Nameless forest, and failing miserably in the attempt. Having learned from my newspaper days that I could barely if at all read any of the scribbles that I made in the dark or half-light while continuing to take in a dance work, I have pared down my notations to those of time by the clock and a word or three as memory aid to recall a precise progression.

This turned out to be superfluous for the most part in recalling the present piece whose striking images and (Ravel’s) Bolero-like sequencing remain so vivid at this writing. Yet the timings reveal such an intricate temporal structure as to rival those of theater director and sometimes choreographer Robert Wilson in their rigor and clarity. Here the potent images and sounds that Burke references in her review, spare as she says, yet pregnant with a raw resonance that Wilson’s striking, stylized, polished and highly technically produced spectacles often lack for me do indeed linger.

My Dancing Matters colleagues confirmed later that they too, as audience, consistently had time to collect impressions, process, and allow associations, images and experiences from their own lives to rise up within them even as the pace of Moss’ looping variations increased in physical force and seeming sense of impatience. I will share a few that persist for me and the context in which I conjured their resonance in a personal way:

- After unwrapping his bundle and exposing the sculptural pyramid mound, Moss wrestles his sailcloth around the stage to unfurl it across the floor with what had been its interior side facing the ceiling and sits on it with his legs splayed out near one end of its length. In the brief but stage-long stillness that follows, his figure calls to my mind that of the solitary sailor in Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream (1899).

- The black stripes in parallel lines that run the length of the sailcloth on which Moss sits reminded me of various versions of the American flag I have seen from Jasper Johns to Black and White to distressed. I have also seen a grayscale half close up photographic portrait of Moss as a child standing alone and saluting an in his face American flag with his right hand over his heart.

- The dragging of the sailcloth bundle, its heavy cotton unfurling, and the repeated regathering of it between his splayed legs as he sits; his repeated twisting of it and retying into a bundle that variously becomes a compacted burden carried on his back, on his head, as a kind of proto straitjacket around his body, finally as a centrifugal counterweight. Working all that cotton, the ropes, the exhausting repetitiousness of the tasks he seems to compel himself to complete in such deliberate fashion.

Art making has its Sisyphean aspect. Having finished a work, one descends the hill to begin another.

In a final sequence Moss asks matter-of-factly if anyone in the audience will help him. His repeated requests and our initial passive and silent response reminded me of an almost daily occurrence and encounter I have on the subway and sometimes on the street. On about the third try, several people in the audience respond and Moss, on this evening, selects a relatively young bearded white man from among those few who volunteer. As this stalwart naif enters the playing area, Moss begins to describe the ordeal that awaits the stranger involving being wrapped up and then dragged “for a looong time.” The young man walks back towards his seat. It turns out that he wants simply to unload his glasses and jacket before this undertaking.

Their interaction takes on a comic edge that seems unforced and evokes a glimmer of touching mutual vulnerability. Moss manages to keep it somewhat dark as he promises to leave his volunteer in that state without light and disappear. The ordeal turns out to be much more mercifully gentle and brief than threatened. Still we sit as witnesses while an older black man in 2023 drags a younger white man around in his sailcloth while a shrouded figure in red orange shag struggles to its feet from under a chair. Moss, having left the young man as he warned, lifts the figure, cradling the phantom in his arms as he disappears through the door toward the parish hall at the northeast corner of the nave and closes the portal behind them. Stephen Vitiello’s magical intermittent recorded score has disappeared one final time.

The denouement as in other Moss works, has a decidedly ambiguous tone and leaves the audience confused as to how to respond. As promised, we have been left in the dark, abandoned with no applause cue and no return of the credited performers. From where I sit, Angela Dufresne’s painted portrait of a seated Moss in costume with hanging black and white striped linen behind and surrounding his image stares back at me from its easel atop the raised sacristy area at the far end of the nave from me and adjacent to the door that Moss carrying Fukuoka have just exited. It looms over the wrapped figure of our intrepid but hapless volunteer seated in his cocoon on the polished wooden floor. As Carol Mullins’ stage lighting fades and stays down an awkward silence engulfs the darkened room broken by tentative and dispirited applause. I turn to a DM colleague in the adjacent seat in the dark and whisper, “But he told us all what he was gonna do.”

- Published in 2023, Dancing Matters