Rocking the Plaza for Peace

The now thirteen annual reincarnations of the 9/11 Table of Silence Project, conceived and choreographed by Jacqulyn Buglisi and presented each year on the morning of September 11 across the entire main expanse surrounding the fountain at the center of Lincoln Center’s Josie Robertson Plaza, have arguably grown into the artist’s magnum opus.

The work already involved more than 100 dancers in its very first iteration, which marked the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attacks of 2001. This year the 152 dancers, 7 musicians, 5 acapella singers and dozens of support and live streaming staff, security personnel and volunteers of the 13th edition, not to mention ceramic sculptural artist Rossella Vasta and her principal fabricator Fausto Bizzirri, costume designer A. Christina Giannini along with Alessandro Gherardi and assistants must bring the total number of people involved directly in the various manifestations of the production to over a thousand across the life of the project. The dancers alone each year have numbered between 129 and 182 and have included adults of all ethnicities and ages with and without apparent disabilities. The youngest among them would not even have been born on that fateful day 22 years ago.

The project has spawned a commemorative book designed and produced by photographer Paul B. Goode in collaboration with Buglisi Dance Theatre, as well as a comprehensive series of videos by Nel Shelby Productions that document the development of the work year by year. Shelby, like Goode, has been a presence all along, and her annual video translations, livestreamed on Youtube, Facebook Live, and Lincoln Center’s own streaming service have now reached people in 235 countries/territories globally as well as all 50 states in the U.S.

In 2020, in the teeth if the pandemic lockdown, the Arnhold Dance Innovation Fund came aboard as lead financial supporter and the work bloomed anew. A reimagined Table of Silence featured a new “Prologue” limited to 28 dancers to accommodate pandemic restrictions and adding live performance by Daniel Bernard Roumain (DBR) of his “Our Country” and the spoken word composition “Awakening” created and performed by Marc Bamuthi Joseph. These artists reappeared in 2021 with 36 dancers while the “Prologue; Improvisation” section that opened this year’s 9/11 iteration included elements of the 2020 and 2021 reimagined 9/11 Table of Silence Project prologue with DBR but without Bamuthi Joseph.

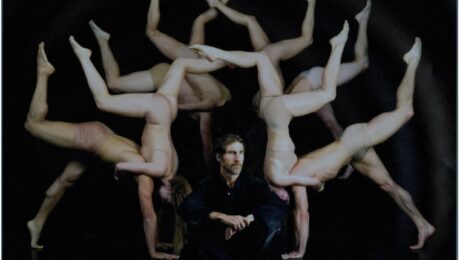

Photo by Josef Pinlac: Visual descriptions of both photos at bottom below.

Lincoln Center has begun, over the course of the pandemic pause, to come to grips with its architectural and social justice legacy. It has, over that time, witnessed both the delayed release of Steven Spielberg’s remake of West Side Story set in a contemporary cinematic recreation of San Juan Hill, the neighborhood the complex supplanted, and the remodeling of what has been renamed David Geffen Hall with artist Nina Chanel Abney’s monumental “San Juan Heal” installed in its uptown-facing façade windows.

In considering the mid-1960’s opening of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in the wake of Robert Moses’ “slum clearance” of a poor but vital neighborhood, New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that “Philharmonic Hall, the State Theater, and the Metropolitan Opera are lushly decorated, conservative structures that the public finds pleasing and most professionals consider a failure of nerve, imagination and talent… Fortunately, the scale and relationship of the plazas are good, and they can be enjoyed as pedestrian open spaces.”

In the decades since Huxtable’s words appeared, I have seen and participated in the use of the fountain plaza for Lincoln Center Out of Doors events, a huge nuclear disarmament demonstration, Midsummer Nights’ Swing, Met Opera film projections, David Michalek’s Slow Dancing installation, an artificial turf hangout, and Carl Hancock Rux’s Juneteenth extravaganza this June 18th, as well as the silent disco that it initiated. I have enjoyed most of these, especially MSNS and the work of the two artists. The art temples have been renamed for billionaires except for the Met. Nothing I have experienced there, however, makes more powerful use of what the American Institute of Architect’s AIA Guide to NYC terms “this travertine acropolis of music and theater” than the 9/11 Table of Silence Project in its most recent incarnation. (Does it seem a predictable omission that dance doesn’t figure in the AIA authors’ characterization of the “travertine acropolis” in spite of the fact that the home of constituent company New York City Ballet has been designed and has generally been used specifically for this discipline?)

Full disclosure: our Dancing Matters group had the privilege of accepting an invitation from Buglisi Dance Theatre to view the proceedings this September 11 from the balcony of David Geffen Hall. I have watched the ceremony unfold from the plaza level about a half dozen times over the years and have always found it moving. Only last Monday did the genius of Buglisi and her collaborators’ design and execution stand fully revealed to me. The choreographer’s use of architect Philip Johnson’s 12 tavertine spokes radiating from the fountain, the plaza at large, and the aprons of the Met and the steps leading up from Columbus Avenue, have developed continually over the life of the project. Last Monday this all seemed to work together with a bare bones but essential power that ultimately draws upon and projects what Buglisi calls the “mandala energy” of Johnson’s design. The intricacies of moving the performers in lines and patterns though and across this expanse maintained a mysterious but palpable tension throughout.

The most stunning revelation on this viewing, however, had to be the way the sound, mostly produced live and only intermittently with the aid of amplification, filled the entire acropolis to match the pulsing presence and movement of the dancers. Particularly effective: the blending of the five female vocal artists intoning their vocalese through large white paper hand-held megaphones. The impression of vulnerable humans set off by a vast formal cityscape found further enhancement in the relation of the Martha Graham reminiscent choreographic designs to the art-temple architecture. Centering this energy, Bell Master/Conductor/Principal Dancer Terese Capucilli and her mirroring bowl ringer and dancer Lauren Jaeger moved with a regal authority that punctuated the proceedings during their cross-fountain duet.

Martha Graham’s fascination with and reimagination of Greek myth from a female perspective proved a potent basis for this dancing. Both Buglisi and Capucilli, as members of Martha’s last company to whom the creator bequeathed queenly roles such as Jocasta, Clytemnestra and Medea, serve as vital links and heirs not only to Graham’s technique but her theatrical imagination. To see Capucilli embody this power and, together with Buglisi, draw this embodiment from within Jaeger, a generation younger, seems to reaffirm its place within a contemporary dance context. On the “tavertine acropolis,” the power of the Greek chorus and the basic elements of sound, sight and movement essential to the conjuring of tragedy toward catharsis could, in this moving ceremony and prayer for peace, all at once be glimpsed and fully felt.

I invite the other members of the Dancing Matters group to comment further as they may wish.

Upper Photo by Terri Gold showing the moment of silent prayer in which the dancers have opened their rounded arms beginning at shoulder level palms and faces lifted skyward in concentric circles on and around the central fountain.

Lower Photo by Josef Pinlac: Visual description: Looking south from a balcony perch, over 100 barefoot dancers in A, Chrstina Giaanini’s white surplices and white tights variously dance around the central black granite topped circle of the Revson fountain across the entire expanse of the Josie Robertson (main) Plaza at Lincoln Center joined by at least two identifiable singers in white holding large white paper acoustic megaphones to their mouths. The fountain burbles at the level of the black granite central disk upon which sit about 3 dozen of Rossella Vasta’s white ceramic dinner plates spaced at regular intervals. Twelve tavertine marble spokes radiate through the otherwise dark grey concrete floor of the plaza crossing four separate concentric tavertine rings each of greater circumference with the smallest hugging the base of the fountain. Visible in the background: broken white clouds in a blue sky over a part of the Midtown Manhattan skyline, the red brick Empire hotel, part of Dante Park, traffic on Columbus Avenue and, bordering the Plaza, the former New York State Theater with large blank muslin projection screens stretched almost entirely across its three main balcony openings. Between audience members lining Columbus Avenue and the plaza stands a line of evenly placed sculptural anti-vehicle barriers. Audience also fills the spaces under the balcony and the muslin screens with a solid line of nuns in white habits occupying half of the next to last portal to the right (west) in the image.

- Published in Dancing Matters

History Meets Its Future

Call it a village; an almost careless yet embracing hospitality. I experienced its warmth the moment I entered through the old wooden red chapel door wreathed with a drone cloud of bumblebees and stood at the north end of the Gothic Revival peaked nave of what began life in 1868 as the chapel and Sunday school of the 1855, renovated 1879, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which stands just to the north on the same campus across a patch of the graveyard that dates to circa 1702 and surrounds both landmarked buildings. Adding another chapter to this history, the chapel has housed BAAD! (Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance) since the venue’s move there in 2014 from the more recently landmarked American Banknote Printing Plant building in Hunts Point where it had pioneered an artists’ community that helped revitalize that neighborhood. Its presence amid the gravestones seemed to both provoke and fulfill a similar promise for the colonial crossroads of Westchester Square and the entire East Bronx.

The easy acceptance of three young children among the multigenerational assemblage of folks in chairs on small risers lining the long walls of the nave on either side of what would become the central performance area enhanced my perception of a sense of community in this space. Facing me, across the long central corridor of the performance area, sat a panel of artist-presenters along the south wall who included host/moderator Aimee Meredith Cox, Melanie George, Millicent Johnnie and Hank Smith. I had walked into the last 20 minutes of the first course of what I had described to my Dancing Matters colleagues as a four-course meal for the soul, only the last segment of which involved actual food.

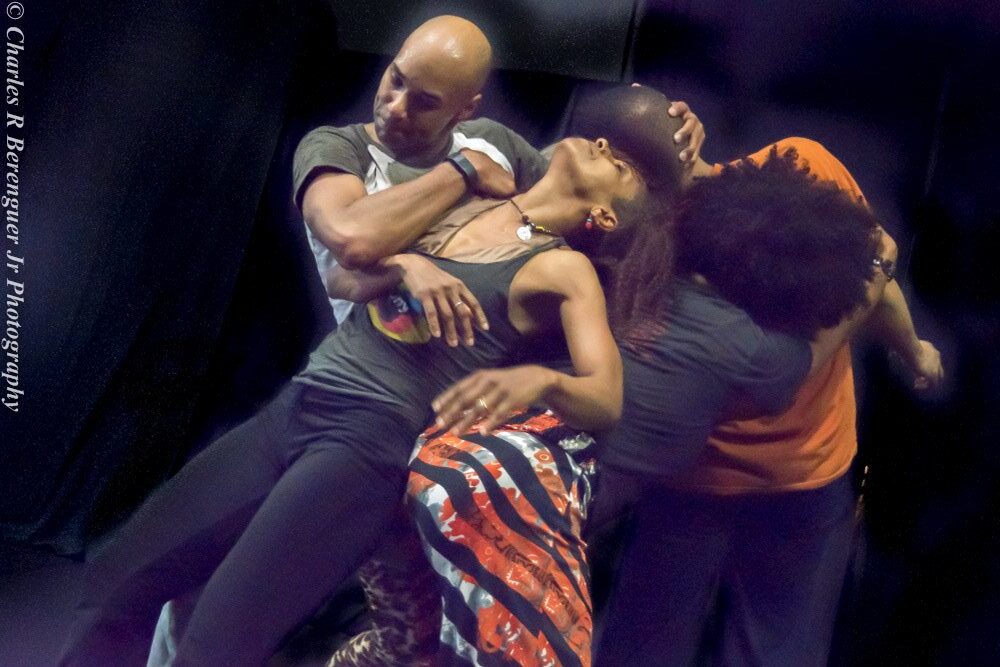

Image description: nia love leans back with Darrell Jones holding her shoulder. She is wearing a black tank top and black pants. He is wearing a gray t-shirt with black short sleeves. Photo by Charles R. Berengeur Jr.

Image description: nia love leans back with Darrell Jones holding her shoulder. She is wearing a black tank top and black pants. He is wearing a gray t-shirt with black short sleeves. Photo by Charles R. Berengeur Jr.

The question the panel along the south wall sought to address: “How has improvisation been a technology for Black thriving?” carried through the entire event and could be said to have been either eleven, 404 years or millennia in formulation. The May 13 unfolding marked the last of a year long celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Dancing While Black series co-directed by Kayla Hamilton, Marguerite Angelica Monique Hemmings, Paloma McGregor and Joya Powell alongside production and thought partner Shalonda Ingram and her team at Nursha Project. The 10th anniversary had begun with a similar three evening series a year ago, which like this year’s edition, began with two virtual presentations followed by a culminating live event at BAAD.

As the members of the panel shared their experiences and thoughts, a just over one year old roamed freely near me in and out of the performance area engaged and contained as occasionally appropriate by not only his mother but by other listeners on either side of the nave, while two somewhat older girls sat, sidled or slid between the knees of other women, one on each set of chairs and risers. The scene, reminiscent of that of a church during the liturgy of the word, served as the hors d’oeuvres.

While this testimony represented only the appetizer, the main course soon arrived as consecration when musician Jocelyn Pleasant on percussion and other instruments called forth the main celebrants Christal Brown, Lacina Coulibaly, Ana “Rokafella” Garcia, Nia Love, Dianne McIntyre, Jason Samuels Smith, and Marlies Yearby to occupy and sanctify the center of the room with an extended structured improvisation. Tolstoy wrote of art as “a human activity consisting in this, that one … consciously, by means of certain external signs, hand on to others feelings <they have> lived through, and that other people are infected by these feelings and also experience them.” Even in the occasional awkward moments this performance manifested from time to time, the cross generational ensemble made these words flesh in ways that increasingly involved sharing with one another as well as those if us watching. In this Smith’s polyrythmic tapping and Rokafella’s breaking lent an extra breadth to the scope to the infectiveness of the dancing, but each of the others added her or his own flavor to the gumbo that we tasted as watchers.

Communion came as a kind of dessert as most of these witnesses became dancers themselves in a two hour dance party with active dj that followed the improvisational presentation. The entire six or more hour event leaned into the sense of communal involvement supportive of exploration within movement that one imagines that more than a decade of the Dancing While Black project has embodied and that the programming at BAAD! seems to epitomize. The full title of this final session had been given as DWB: Future: How We Thrive. As a harbinger of a possible post pandemic arts ecology the title seemed apt and its generous execution pointed with hope to a possible pathway.

As each of the Dancing Matters attendees danced their fill at the post party, we retired in twos and threes for our digestif discussion to the Mexican place that BAAD! Artistic Director Arthur Aviles had recommended on Westchester Square, one of seven La Estrellita’s whose burgeoning success hints at so much about the long slow recovery from lockdown evident in the New York City of this moment. We had invited the artists to join us at dinner and welcomed Rokafella along with her husband and partner Kwikstep to our table. Bronxite Rok did the majority of the ordering en español.

BAAD! and its borough might be seen as a place of pilgrimage among a large portion of the audience for live dance much as former Jacob’s Pillow Artistic Director Liz Thompson once characterized her campus in Becket, Massachusetts, that transfigured an old New England farm. One of our number intimated, in the course of our sojourn, that the last time he’d visited Westchester Square had been to leaflet against the draft during the U.S. war in Vietnam. I thought about that as I explored the cemetery surrounding BAAD! and St. Peters that contains graves from every U.S. conflict since its inception as well as about Myanmar, Sudan and Ukraine.

To arrive here for this extraordinary adventure from Brooklyn, one had had to allow for weekend subway work that had the number 6 train terminating at Parkchester, three stops short of East Tremont/Westchester Square. Our group, however, had shown the determination to reach this transformed village to embrace its history and unfolding future and be embraced by it in return. Mark Twain wrote of travel as, “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts.” Travel, like dancing, involves movement. I hope that my DM colleagues found this travelling as moving as I did, and maybe, whether they have or not, they will say so in writing on our Facebook page.

- Published in Dancing Matters

Momixing It Up

Moses Pendleton’s Momix, which he founded in 1980, while still creating as one of the cofounders of the cooperative ensemble Pilobolus, represents that rarest of species in American dance: a for profit company. An online search turned up nary another and an inquiry to Dance USA’s Director of Research set her off on a fruitless search for any others beyond the dance school and dance competition models.

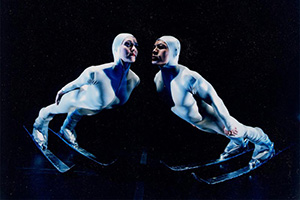

A female dancer (left) and male dancer (right) each lean sharply forward in extreme diagonals their feet anchored on skis, their bodies sheathed in full form-fitting long sleeved unitards complete with tight hoods tinted blue in the stage lighting against a deep black background and covering all but their faces which almost touch in Moses Pendleton’s “Millenum Skiva” created for his company Momix. Photo by Freddy Fernandez.

A female dancer (left) and male dancer (right) each lean sharply forward in extreme diagonals their feet anchored on skis, their bodies sheathed in full form-fitting long sleeved unitards complete with tight hoods tinted blue in the stage lighting against a deep black background and covering all but their faces which almost touch in Moses Pendleton’s “Millenum Skiva” created for his company Momix. Photo by Freddy Fernandez.

This may seem surprising, but perhaps it shouldn’t when one considers that Pendleton, ever the maverick, claims the fountainhead of his career as a showman as having been the Caledonian County Fair in the Northeast Kingdom of his native Vermont. Here he would exhibit his family’s dairy cows. Don’t know whether the family won any prizes and, if not, it surely could not have been for a lack of presentational skills. Pendleton’s been putting fanciful imaginary creatures (no cows that I know of) on stages across the globe for the last fifty years plus.

In a brief conversation in the aisle after the show, Pendleton proved as skeptical of dance community pieties as he always seems to have been. What becomes interesting then has to do with his singular creative focus on the locus of the human body in reimagining a universe based on the one we physically share with all other creatures and energies on earth.

The breadth of the appeal of his approach can be witnessed not only in the longevity of the Momix project on a touring and commissioning model that went out of style and functionality, if not at the demise of vaudeville, then just about the time that Pilobolus broke onto the scene, but also in the universal enchantment among the eighteen other Dancing Matters folks with whom I shared the experience. More importantly, I find it in the faces of the many children present. If this represents their introduction to dancing as a mode of expression, the kids might do as well with hip hop and/or the traditional dance cultures that Queens, the most immigrant rich borough among the five of an immigrant embracing and creatively energized city, brings to them. But in terms of stretching their imaginations, it might be hard to do better.

The show itself, so much a draw that Queens Theatre Director of Community Engagement Dominic D’Andrea remarked in a curtain speech that he couldn’t remember a larger Saturday matinee audience since the beginning of the pandemic, proceeded in bite sized pieces, perfect for kids and their parents. Most of these excerpts, drawn from the six shows that Momix currently claims as repertory, lasted between 3 and 4 minutes. They therefore represent a greatest hits collection of moments in medley and montage that almost insures its popularity and the overall length of show can prove both a blessing and a challenge to the audience described. Interestingly, “Paper Trails,” my personal favorite among these tidbits, occurring just before intermission, left a preponderance of the younger children asleep in their seats, exhausted, I presume, by the unfolding pageantry of the first half, the black light darkness and the lullaby quality of the mixtape score which included “Good Bye Brother” by Ramin, Djawadi: “Progeny” by Yvonne Moriarty, Gavin Greenway and the Lyndhurst; “Sorrow” by Klaus Badelt and Lisa Gerrard; “Wisdom Work” by Byron Metcalf.

Pendleton fronts an eclectic musical vocabulary to accompany his pieces ranging from contemporary sound artists such as these with Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major for the big finale. Let’s celebrate life!

I leave it to my Dancing Matters colleagues to overcome their shyness in responding in this democratic written critical discussion forum to speak up about the many other segments that they told me they adored in our round-table-picnic-in-the-park-post-performance confab, Queens Night Market having been cancelled as our ultimate destination that evening.

- Published in Dancing Matters

Crazier Than You

I

The late Bob Fosse invoked someone at the 1987 Tony Awards presentation, the year that he died at 60, as he introduced Gwen Verdon, still his wife, co-parent and longest-running muse and collaborator. As he phrased it, “It’s been said that the art of choreography is only 50% conception. And that the real test of your talent is getting five or six or however number of people in a room who are just a little crazier than you are and who can try to live out that, ah, that thing in your head. Sometimes, if you’re very lucky, you can find someone who dances it better than you ever dreamed it.”

The very present Elizabeth Streb, now 72, dreamed it, yes, and in many cases also danced it herself when first introduced. But as the evolving “Time Machine” program reveals, she has been very lucky indeed for some time and remains so.

The present company, billed as Action Heroes although I’ve heard Streb refer to them as dancers in rehearsal, retains only Co-Artistic Director Cassandre Joseph-Donnelly and Senior Action Hero Jackie Carlson from among the seasoned cast of eight who premiered the first iteration of this “Streb’s greatest hits” compendium on the outdoor stage at Jacob’s Pillow in mid-August, 2021. This pair may have been in grade school or younger when Fosse spoke. They almost certainly had not been born when Streb first performed Pole Vault and 7’43” in 1978, the oldest two pieces (billed Action Events) on the program that the Dancing Matters (DM) group took in on Saturday, March 25; the second show of “Time Machine’s” nine week run in the company’s home season in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I doubt that Streb could have dreamed of two more crazily accomplished and dedicated people to dance it any better.

Jackie Carlson in “Pole Vaults” Photo by Stephanie Berger

Visual description: Jackie Carlson, a pale skinned dancer (she/he/they) with a bright blonde fade haircut, black tank top with a large white and red Streb Action Hero “S” on the front, white Streb leggings printed in black and orange, and an orange stirrup wrap on her right ankle leans forward on her tippy toes against a 4 foot long closet dowel, spiral wrapped in yellow and dark green , balancing against their navel and the bare orange floor of SLAM. Behind him, in front of a cinder block wall, square open-latticed black metal apparatus legs frame a pattern of red, yellow, blue, white and smaller black squares surrounding 4 rectangular video screens. Thick red mats cover an adjacent part of the floor in front of a member of the tech crew behind a red console.

Joseph-Donnelly and Carlson have been with the company since 2007 and 2008 respectively. They lead an equally committed group listed as three other core company members, each of whom took on a solo in this program, alongside five other Action Heroes, at least three of whom joined the troupe in 2022. You could’ve fooled me.

In a former avocation as a jayvee college hockey player, heads-up team play meant everything to me when bladed sticks, hard rubber frozen disks and sharpened skates would be involved at maximum speed. The Action Heroes have many more objects of concern keeping them in sync and focused. They also seem to have had better practices than we did.

I like to roam whenever I can while taking in a performance, constantly seeking out the best angle with which to see the whole bodies of performers, including feet, as well as the audience in its moods and reactions. In this, the Streb Lab for Action Mechanics (SLAM) layout, in what had been an industrial loading facility, proved most accommodating. The sometimes bemused smiles and rapt attention I observed from the crowd, including those of not only my Dancing Matters colleagues but also that of a girl of no more than four in the first row on an adult woman’s lap, presaged the highly positive observations and occasional wonderment that characterized the DM post-performance discussion over bites and sips at the nearby Williamsburg Market.

Jackie Carlson (horizontal in bungee harness) pulled by other Streb Action Heroes in “Kiss the Air” finale.

Visual description: Jackie Carlson, a pale skinned dancer (she/he/they) with a bright blonde fade haircut, wearing a black tank top, white Streb leggings printed in black and orange, hangs horizontally at a slight diagonal, pointed toes up and head lifted at the neck toward 3 other similarly clad mixed race Streb Action heroes. Their feet just off the red mat over which s/he hangs in a bungee hip harness, the 3 other Heroes grasp her arms and pull her toward the audience directly behind them. About a dozen young children sit on the floor in the front row, some being protected by a brown skinned young man in black who reaches across them with his right arm to shield them while confetti fills the air, adults behind them smile and three of the adults hold up their cell phone cameras. screens. A white 12 foot wall stands behind the audience reaching part way to the ceiling while another Action Hero, a yellow “S” on his long sleeved t-shirt above yellow leggings and his face obscured holds an apparatus controller at the end of a yellow power cord.

The show reminded one member of a visual artist’s retrospective. Another compared the program to an evening of cinema short subjects. The group discussed another member’s irritation at the way the Action Heroes off the playing area would vocally encourage one another, particularly during solos. Having represented a fairly chirpy bench presence during hockey games, these interjections sounded refreshingly familiar to me.

The ”Time Machine” series continues Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, through May 21st, at the Streb Lab for Action Mechanics (SLAM) in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Action Hero rehearsals there remain free and open to the public in keeping with the Streb Extreme Action tradition of opening SLAM to the entire community to the maximum extent practicable.

- Published in Dancing Matters